Reality Check Are You Awake or Asleep?

Ceo and founder OF WAKE OUR MINDS BACK SPIRITUAL

Empress Tont'e Fairfax

WOMEN OF MELANIN BEAUTY STANDARDS/ REALITY CHECK ON BLACK HAIR

In the 1600s-1700s, head shaving was one of the cruel indignities that slaves’ suffered. This was meant to erase identity and culture. If white women were jealous of their female slave’s hair, they would force them to cut it off. In 1786 the Governor of New Orleans enacted the Tignon Law. It required Black Women to cover their hair with scarfs to indicate their class. Black Women appropriated this law by cover their hair, lavishly gorgeous fabric, and jewels. In the 1800s, slaves would often use butter or goose grease to moisturize their hair. They would also use carding tools to comb their hair.1860’s to the 1900s in the decades following emancipation.

Black people faced economic and social pressure to assimilate into white culture. Some began to alter the texture of their hair with chemicals. Black people continue to straighten their hair because of the perpetuated belief that coiled or kinky hair was unattractive. Conforming to white culture was seen as necessary for employment and to avoid abuse. In the 1920s, Josephine Baker helped popularize the iconic” flapper” look. Many women followed suit by cutting their hair short, which some interpret as a rejection of traditional female roles. Also, finger waves were popular in this era. In the 1950s, Black women were wearing wigs to match fashion trends they could not produce with their own hair. In the 1960s, during the civil rights movement, Black people grew their afro’s out as a symbol of pride and rebellion. Sales of straightening chemicals and hot combs declined in the ’60s, coinciding with the Black Power movement’s support of natural hair.

In 1972 Cicely Tyson popularize corn roles in the US while promoting sounder. In the 1980’s the origins of dreadlocks cannot be traced, but there is evidence of the style Ancient Egyptian, Viking, and pacific islander cultures. In 1985 Whoopi Goldberg popularized dreadlocks grown for non-religious reasons. A new perm formula was introduced in the ’80s creating the Jheri curl. To maintain the look, people with Jheri curls had to use activators and heavy moisturizing creams. In the ’90s, although braiding hair has been part of Black culture for centuries. Janet Jackson brought box braids mainstream culture in iconic movie Poetic Justice. In the past, slaves did not have a choice, but today you do. “We are still following trends instead of looking from within.”

We were the most respected and desirable women in the world for many centuries. Today we are the most disrespected and undesirable women to the black man. The reason some women cannot find a Black man is because she is a fake white woman. That’s why black man prefers the authentic white women.

As a woman of color, being born with melanin is beauty in itself. I feel genuinely grateful knowing. I have melanin. That nourishes my skin with vitamin D and natural healing.

WOMBS without melanin, we would age faster, and the sun would be our enemy. We are losing our identity by following what society considers beautiful. As a woman of color, we have a right to look the way God intended. We are covering and straightening our crown, which makes us unique from all other races. Our nappy-kinky hair has a Spiritual Connection to the universe, that has been kept away from us for centuries. Energy flowing through spiral hair will enter the millions of nerve-paths, leading to the brain and, ultimately, the pineal gland.

WOMBS, we are wasting our hard-earned money following today’s beauty standards. We are turning our healthy hair to weak and thin hair. By straightening our hair, pressing it, perming it, wearing wigs, weaves, hair dyes. To make yourself feel beautiful to attract men. Some men prefer natural hair over fake hair.

WOMBS, some of you are doing too much, with the long fake eyelashes and bright colored contact lenses. Just when you thought it could not get any worse, we are bleaching our skin, cutting off our eyebrows to draw on fake ones. We have not finished spending our hard-earned money yet; we have to get our eyebrows waxed, eyebrows dyed, wax our vagina, pedicures, manicures, wearing name brand clothes, shoes and purses. After all the money spent on material things, you are still lonely and depressed.

As a QUEEN, we should not care what other people think about us; we are trendsetters, leaders, and not followers. There is nothing wrong with our natural beauty; there is something wrong with what we think is beauty. Until we learn to love ourselves, we will continue to feel depressed, stressed, waste money, feeling jealousy, envy, anxiety, following trends, self-hate, attract negative people, and unhealthy relationships. The problem is your thinking. If you don’t love yourself, why should anyone else? Learn to love the skin you’re in, and your new love life can begin.

Wombs, we are always looking for a real man, when our entire image is fake. We must learn to embrace our melanin beauty standards. QUEENS look around; everyone wants to what’s to be you except you. That’s why knowledge is power, and what you don’t know can hurt you.

How may I help you?

Please let me know what services interest you.

Comedy Events

Comedians and Comediennes in Charleston and surrounding areas.

Women of Melanin Beauty Standards

A place for women of color to express their views. While learning self love, healthy eating, healthy living, love, relationships and much more.

Personalize T-Shirts

Let your shirt express your personality

What Happened

When Blacks Supported

Black Businesses?

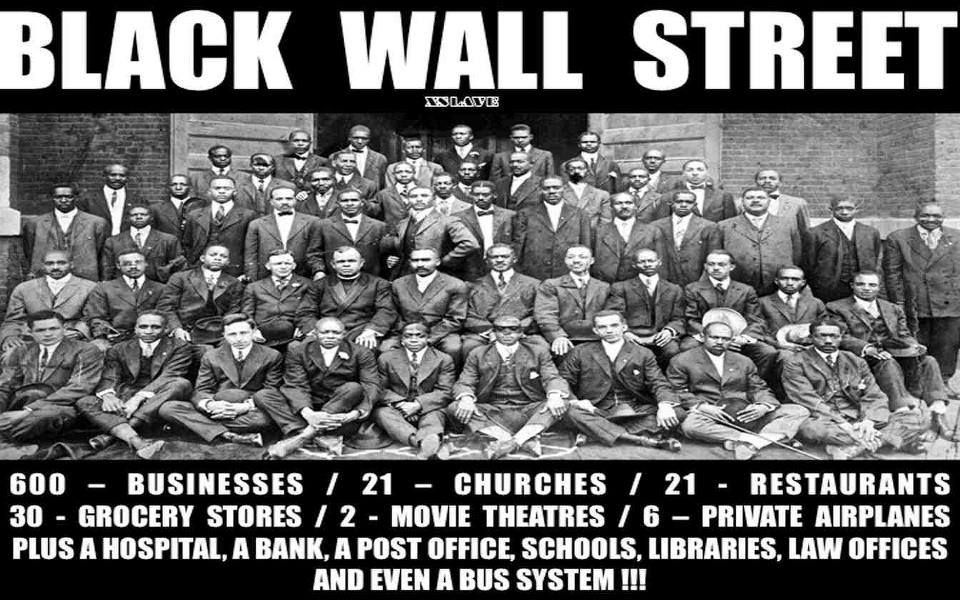

‘We lived like we were Wall Street’

Before the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Greenwood was one of the wealthiest black communities in the country. Before it was destroyed in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Greenwood was one of the most affluent black communities in the country. It was known as “Black Wall Street” because of its concentrated wealth.

“We lived like we were Wall Street,” remembered Otis Granville Clark, then a 105-year-old survivor of the massacre, in “Before They Die!,” a 2008 documentary. “A lot of folks would come in from New York and Chicago. We had a big time here on Greenwood. This was oil country.”

Greenwood’s past is back in the news after Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum (R) announced last week that the city would reopen its investigation into whether victims of the century-old race massacre were buried in mass graves.

Before the massacre, Greenwood had a population of more than 100,000 black people, according to the Greenwood Cultural Center’s history of the community. It was home to luxury shops, 21 restaurants, 30 grocery stores, a hospital, a savings and loan, a post office, three hotels, jewelry and clothing stores, two movie theaters, a library, pool halls, a bus and cab service, a nationally recognized school system, six private airplanes and two black newspapers.

Jim Crow kept that wealth in the community. “Not only did black Americans want to contribute to the success of their own shops,” the cultural center explains, “but there were also racial segregation laws that prevented them from shopping anywhere other than Greenwood.Elegant homes where doctors, lawyers and business owners lived lined Detroit Avenue.

Olivia Hooker, who was 6 at the time of the massacre, recalled that her father, Samuel D. Hooker, owned a department store, selling clothing and other goods.

“I was a child who didn’t know about bias and prejudice because the only white people we saw came to sell things to my father,” Hooker, now 103, said in an interview with The Washington Post. “They were very nice. It was quite a trauma to find out people hated you for your color.”

Her mother hid her and her siblings under a dining room table as their home was being ransacked.

“They took everything they thought was valuable. They smashed everything they couldn’t take. My mother had [opera singer Enrico] Caruso records she loved. They smashed the Caruso records.“At the time of the riot, there were fifteen well-known black American physicians, one of whom, Dr. A.C. Jackson, was considered the ‘most able Negro surgeon in America’ by the Mayo brothers,” founders of the Mayo Clinic, according to the Greenwood Cultural Center. Jackson was fatally shot during the massacre when he emerged from his house with his hands raised in surrender to the mob. Walter F. White, then assistant secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, said in an interview that appeared in a June 18, 1921, Salt Lake City newspaper:

“Having been sworn in as a deputy sheriff and having been on patrol as such during the Tulsa riot, I am able to state that the Tulsa riot in sheer brutality and wilful [sic] destruction of life and property stands without a parallel in America.”

White, a black man whose skin color was such that he was able to slip into white communities to gather information, traveled the country in the early part of the century investigating lynchings and mass murders of black people.

The massacre began on May 31, 1921, when white mobs descended on Greenwood, burning houses and shooting black people. Some people were burned alive, and 40 square blocks of business and residential property — valued then at more than $1 million — were destroyed.

During the Tulsa Race Massacre (also known as the Tulsa Race Riot), which occurred over 18 hours on May 31-June 1, 1921, a white mob attacked residents, homes and businesses in the predominantly black Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The event remains one of the worst incidents of racial violence in U.S. history, and one of the least-known: News reports were largely squelched, despite the fact that hundreds of people were killed and thousands left homeless.

Black Wall Street

In much of the country, the years following World War I saw a spike in racial tensions, including the resurgence of the white supremacist group the Ku Klux Klan, numerous lynchings and other acts of racially motivated violence, as well as efforts by African Americans to prevent such attacks on their communities.

By 1921, fueled by oil money, Tulsa was a growing, prosperous city with a population of more than 100,000 people. But crime rates were high, and vigilante justice wasn’t uncommon: In August 1920, a white mob took a white teenager accused of murdering a taxi driver from his jail cell at the courthouse and lynched him; newspaper reports claimed the police did little to prevent the lynching.

Tulsa was also a highly segregated city: Most of the city’s 10,000 black residents lived in a neighborhood called Greenwood, which included a thriving business district sometimes referred to as the Black W

What Caused the Tulsa Race Massacre?

On May 30, 1921, a young black teenager named Dick Rowland entered an elevator at the Drexel Building, an office building on South Main Street. At some point after that, the young white elevator operator, Sarah Page, screamed; Rowland fled the scene. The police were called, and the next morning they arrested Rowland.

By that time, rumors of what supposedly happened on that elevator had circulated through the city’s white community. A front-page story in the Tulsa Tribune that afternoon reported that police had arrested Rowland for sexually assaulting Page.

As evening fell, an angry white mob was gathering outside the courthouse, demanding the sheriff hand over Rowland. Sheriff Willard McCullough refused, and his men barricaded the top floor to protect the black teenager.

Around 9 p.m., a group of about 25 armed black men—including many World War I veterans—went to the courthouse to offer help guarding Rowland. After the sheriff turned them away, some of the white mob tried unsuccessfully to break into the National Guard armory nearby.

With rumors still flying of a possible lynching, a group of around 75 armed blacks returned to the courthouse shortly after 10 pm, where they were met by some 1,500 whites, some of whom also carried weapons.

Greenwood Burns

After shots were fired and chaos broke out, the outnumbered group of blacks retreated to Greenwood.

Over the next several hours, groups of white Tulsans—some of whom were deputized and given weapons by city officials—committed numerous acts of violence against blacks, including shooting an unarmed man in a movie theater.

The false belief that a large-scale insurrection among black Tulsans was underway, including reinforcements from nearby towns and cities with large African-American populations, fueled the growing hysteria.

As dawn broke on June 1, thousands of white citizens poured into the Greenwood District, looting and burning homes and businesses over an area of 35 city blocks. Firefighters who arrived to help put out fires later testified that rioters had threatened them with guns and forced them to leave.

According to a later Red Cross estimate, some 1,256 houses were burned; 215 others were looted but not torched. Two newspapers, a school, a library, a hospital, churches, hotels, stores and many other black-owned businesses were among the buildings destroyed or damaged by fire.

By the time the National Guard arrived and declared martial law shortly before noon, the riot had effectively ended. Though guardsmen helped put out fires, they also imprisoned many black Tulsans, and by June 2 some 6,000 people were under armed guard at the local fairgrounds.

Aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre

In the hours after the Tulsa Race Massacre, all charges against Dick Rowland were dropped. The police concluded that Rowland had most likely stumbled into Page, or stepped on her foot. Kept safely under guard in the jail during the riot, he left Tulsa the next morning and reportedly never returned.

The “official” tally of deaths in the massacre was 36 people killed, including 10 whites. Even by that estimate—which historians now consider much too low—the Tulsa Race Massacre stood as one of the deadliest riots in U.S. history, behind only the New York Draft Riots of 1863, which killed at least 119 people.

In the years to come, as black Tulsans worked to rebuild their ruined homes and businesses, segregation in the city only increased, and Oklahoma’s newly established branch of the KKK grew in strength.

READ MORE: How ‘The Birth of a Nation’ Revived the Ku Klux Klan

News Blackout

For decades, there were no public ceremonies, memorials for the dead or any efforts to commemorate the events of May 31-June 1, 1921. Instead, there was a deliberate effort to cover them up.

The Tulsa Tribune removed the front-page story of May 31 that sparked the chaos from its bound volumes, and scholars later discovered that police and state militia archives about the riot were missing as well. As a result, until recently the Tulsa Race Massacre was rarely mentioned in history books, taught in schools or even talked about.

Scholars began to delve deeper into the story of the riot in the 1970s, after its 50th anniversary had passed. In 1996, on the riot’s 75th anniversary, a service was held at the Mount Zion Baptist Church, which rioters had burned to the

all Street.

ground, and a memorial was placed in front of Greenwood Cultural Center.

Tulsa Race Riot Commission Established, Renamed

The following year, after an official state government commission was created to investigate the Tulsa Race Riot, scientists and historians began looking into long-ago stories, including numerous victims buried in unmarked graves.

In 2001, the report of the Race Riot Commission concluded that between 100 and 300 people were killed and more than 8,000 people made homeless over those 18 hours in 1921.

A bill in the Oklahoma State Senate requiring that all Oklahoma high schools teach the Tulsa Race Riot failed to pass in 2012, with its opponents claiming schools were already teaching their students about the riot.

According to the State Department of Education, it has required the topic in Oklahoma history classes since 2000 and U.S. history classes since 2004, and the incident has been included in Oklahoma history books since 2009.

In November 2018, the 1921 Race Riot Commission was officially renamed the 1921 Race Massacre Commission.

“Although the dialogue about the reasons and effects of the terms riot vs. massacre are very important and encouraged,” said Oklahoma State Senator Kevin Matthews, “the feelings and interpretation of those who experienced this devastation as well as current area residents and historical scholars have led us to more appropriately change the name to the 1921 Race Massacre Commission.”

Sources

James S. Hirsch, Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its Legacy (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2002).

Scott Ellsworth, “Tulsa Race Riot,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

1921 Tulsa Race Riot, Tulsa Historical Society & Museum.

Nour Habib, “Teachers talk about how black history is being taught in Oklahoma schools today,” Tulsa World (February 24, 2015).

Sam Howe Verhovek, “75 Years Later, Tulsa Confronts Its Race Riot,” New York Times (May 31, 1996).

We support all other businesses except our own. While other people only support their people. There is differently something wrong with this mindset.Black owned businesses and entrepreneurs have been longtime wealth builders in our society. By supporting more Black-owned businesses, can create more opportunities for meaningful savings, property ownership, credit building and generational wealth. Strengthens Local Economies

When small businesses flourish, so do their communities. But banks often hinder that prosperity by discriminating against African American and other entrepreneurs of color seeking small business loans. A 2017 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition actually found that banks were twice as likely to provide business loans to white applicants than Black ones and three times as likely to have follow-up meetings with white applicants than more qualified Black ones.

If consumer spending accounts for 70 percent of the entire US economy, imagine what directing some of that spending power to Black-owned businesses across the country can do. 48 percent of small business purchases are recirculated locally compared to only 14 percent of what’s circulated by chain stores. Supporting Black-owned businesses in turn supports families, employees, and other business owners, as well as attracts community investors who provide banking services, loans, and promote financial literacy–all things that build economic strength.